The tech driving ZSG's expansion from 36 to 100 restaurants

Watch extracts

Summary

Patrick De Pinho is a lifelong operator who’s done almost every job in hospitality – chef, restaurant manager, business owner, yacht chef – and today sits in the GM seat at Zeus Street Greek, a 36-site “elevated QSR” brand with an aggressive plan to hit 100 locations by 2028. In this episode, he and Armando unpack what it really takes to standardise a geographically spread franchise, move from emails and Excel to a connected tech stack, and pick vendors who are built by operators for operators. Patrick shares how centralising data has helped Zeus Street Greek uncover six-figure opportunities in COGS, including a halloumi variance worth $500 a week in a single store and a chips recipe that looked great on paper but short-changed guests in reality. Throughout, he comes back to two themes: technology only works if it makes life easier for the people using it, and scaling from 36 to 100 sites is as much about curiosity, feedback and human relationships – with teams, franchisees and vendors – as it is about software.

Learnings From The Episode

From 12-year-old chef to “deep in the trenches” GM

Patrick has been “hospo all my life.”

- He started cooking at 12, taking a school-holiday job in the Air Force HQ in South Africa where his dad worked.

- From there he moved through almost every corner of hospitality: restaurants, hotels, yachts, restaurant management, and small business ownership.

- He’s been “in the trenches” for 25+ years – on the pans, on the floor, in the office.

That experience is the lens he now brings to Zeus Street Greek. He may not be on the tools anymore, but the empathy and pattern recognition from decades of service are what make him effective today: when he looks at a system or a process, he’s thinking first about the person on the grill or at the pass trying to use it in the middle of a rush.

What Zeus Street Greek is actually building

Zeus Street Greek just turned 10. On paper, they’re “Greek street food” with 36 locations across Australia. In practice, Patrick frames them as an elevated QSR with four growth pillars:

- Retail (bricks & mortar):

- 36 stores, across all major states except South Australia.

- 11 are corporate-owned; the rest are single or multi-site franchisees.

- Positioning on value and quality:

- They deliberately play the middle: strong value without sacrificing quality, which is central to their plan to grow from 36 to 100 stores by 2028.

- FMCG / retail products:

- To build brand awareness beyond areas where they have restaurants, Zeus is moving into major retailers with branded products – meeting customers who’ve never set foot in a store.

- IT and data as a growth pillar (not a back-office chore):

- The most important pillar in Patrick’s eyes: a clear tech strategy and connected systems that support that journey from 36 to 100 sites.

The goal isn’t just more stores. It’s a network where standards, guest experience, and profitability all scale together.

Standardising a 36-site, multi-state franchise

Zeus operates a franchise model with central standards and local operators.

Head office owns:

- Menu development

- Supply chain management

- Core operating systems

But reality on the ground is messy:

- Even with a central supply chain, prices and availability vary by state – transport costs, local sourcing, and “natural forces” all play their part.

- HQ runs a lean team; they can’t be everywhere at once. Operations teams have to “divide and conquer” their time and still make every store feel supported.

Standardisation isn’t only about a spec sheet. It’s about having the visibility and touch points to see where standards are drifting and the capacity to help store teams close the gap.

Why email and Excel broke at scale

When Patrick joined Zeus Street Greek about 18 months ago, he started as New South Wales state manager for corporate stores – with projects on the side.

Eight months in, the job turned into full-time project and systems work.

Why? Because running 36 sites on:

- Emails

- Excel spreadsheets

- Ad-hoc reporting

…wasn’t sustainable anymore.

They found:

- Too many businesses (including Zeus) still relied on spreadsheets and email threads to run multi-million-dollar operations.

- With dozens of people touching those files, you end up with version control nightmares, inconsistent logic, and no single source of truth.

- You can’t meaningfully benchmark stores or spot patterns in labour, COGS, or waste when your “system” is a patchwork of manual inputs.

For Zeus, it became obvious that if they wanted to get to 100 stores, the operating system had to change first.

Choosing technology: operators building for operators

Patrick is very clear: he’s not a technologist by background. He’s an operator leading tech change.

That’s exactly why he cares so deeply about who he partners with.

What he looks for in vendors:

- Built by (or with) hospitality operators:

Vendors who’ve run sites themselves, or employ people who have, understand the quirks of service, the realities of stock night, and the chaos of Friday dinner. - Honesty about scope:

He prefers partners who are candid about what they don’t do, instead of pretending to be good at everything. - Tech that serves people first, HQ second:

The tools must support the people using them every day – managers, chefs, franchisees – not just spit out dashboards for head office.

In Patrick’s world, “best of breed” means:

let POS be POS, inventory be inventory, labour be labour – and then make them work together.

Connecting a best-of-breed stack through a central brain

Rather than buying one “do-everything” system, Zeus has gone the Lego-brick route:

- Specialist POS

- Specialist inventory management

- Specialist labour management

- Training and communication tools

- A central business intelligence layer

The key is what happens between them:

- Sales data feeds into inventory and labour.

- Inventory usage and recipe costing feed into profitability views.

- Everything rolls up into a central BI tool that gives HQ a holistic view of the network.

The question for Zeus isn’t “How many systems do we have?” It’s:

“Do these systems talk to each other so we can see the truth in one place?”

Human relationships > feature lists

For Patrick, the most important part of any tech partnership is the relationship.

He compares it to buying a car:

- No one wants a brand-new car with 20-year-old tech.

- But just as important: when something breaks, you need to know there’s someone on the other end of the phone who will help you fix it.

What he values in vendors:

- People he can call when something isn’t working – not just a ticket system.

- A willingness to say “we don’t do that yet, but we can help you get close” or “we’ll build it with you.”

- Partners who are evolving their own product so Zeus can scale with them over years, not months.

Change management, in his view, is 90% people and only 10% software. If you don’t have that human partnership, the tech will eventually go stale.

Designing tech people actually want to use

Zeus employs a generation that “grew up with technology in their hands.”

If you want to:

- Attract strong franchisees

- Attract smart GMs and crew

- Keep them engaged

…you have to give them tools that feel modern.

For Patrick, that means:

- Mobile-first experiences:

Managers shouldn’t be stuck in an office with a desktop. Ordering, stock counts, labour sign-off, feedback – as much as possible should live on the phone. - Fast admin:

Placing an order, receiving a delivery, reconciling a day’s sales or labour – these should be “a few minutes” jobs, not half-day slogs. - Training delivered where people already are:

Zeus uses AI-driven training and knowledge tools that behave like WhatsApp – chat interfaces that staff are comfortable with, backed by a central knowledge base.

The litmus test he uses internally:

does this tech give people more time to deliver food and service, or does it drag them away from guests?

Working with franchisees: carry the risk first

Zeus’ franchise agreements give them the right to choose and change core operating systems. But they’re deliberate about how they exercise that right.

Their approach:

- Corporate carries the risk first:

New systems are piloted and stress-tested in corporate stores before they roll out to franchisees. - Franchisee Advisory Board:

A representative group of long-term and newer franchisees that meets regularly to discuss marketing, pricing, and tech decisions. - Always explain the “why”:

Changes aren’t handed down from HQ as diktats. Patrick’s team shares the rationale – how a new tool supports profitability, visibility, or guest experience.

The goal is not just compliance. It’s co-ownership of decisions that ultimately affect franchisees’ livelihoods.

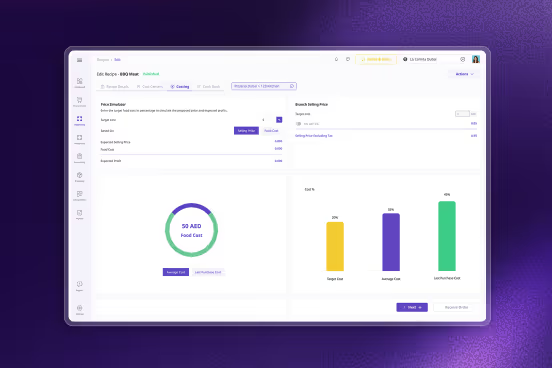

How better inventory visibility turns loss into margin

Two of Zeus’ biggest cost lines are labour and COGS. Without good inventory data, COGS is blind.

A concrete example: halloumi.

- In one pilot store, repeated stock counts showed halloumi missing at a meaningful scale.

- When they went into the operation, they discovered:

- Training was outdated.

- The crew were over-portioning – almost double the intended amount.

The impact:

- Roughly $500 per week in loss on just one product in one store.

- Fixing training and portioning not only improved margins but, when scaled across the network and time, equates to hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Without a dedicated inventory system and live variance reporting, that pattern would have stayed hidden inside a spreadsheet for years.

When the recipe is wrong, not the team

The chips story shows the flip side: sometimes the issue isn’t behaviour, it’s configuration.

In the same store:

- Chips usage and variance looked terrible.

- The assumption might have been: “the team are giving away too many chips.”

Instead, they ran a simple test:

- Weigh the “small” and “large” scoops used in store.

- Compare them to the recipe costing in the system.

What they found:

- The store was portioning correctly.

- The recipe in the system was wrong – set at roughly half the actual serving size.

If they’d blindly “fixed” the variance by forcing teams to follow the recipe as written, guests would have received half-portions and felt cheated. Instead, they:

- Updated the recipe to match reality.

- Saw an ~80% improvement in chips variance.

- Aligned data with guest experience rather than the other way around.

That’s the power of live data plus operator judgment: spotting where the spreadsheet is lying and correcting it in favour of both guests and profitability.

Mobile tools, AI training and freeing managers from the back office

Zeus has redesigned workflows so that as much as possible happens on the move:

- Stock counts:

Previously: 3.5–4 hours, two people, often late at night.

Now: under two hours, sometimes under an hour, with a logical left-to-right, top-to-bottom flow through the store on a mobile device. - Ordering:

A manager can walk into cold storage, say “I need tomatoes, cucumbers, pork, chicken,” and have the system handle which suppliers receive what. - Menu and safety:

Temperature checks, food-safety logs, new menu training, labour sign-off – all centralised in tech instead of paper, emails, and ad-hoc documents. - AI knowledge and feedback:

A chat-style interface connected to a central data source answers team questions; if it doesn’t know the answer, HQ can add it once and the system “learns” for next time.

Any team member can submit feedback through the same ecosystem, which HQ then uses to drive change.

The result: less time on admin, more time on guests – and a culture where everyone can see that their input shapes the system.

Garbage in, garbage out: data quality and integrations

The dashboards are only as good as the data feeding them.

Patrick’s priorities here:

- Sales data as the anchor:

Revenue numbers must be accurate; everything else (COGS, labour %, margins) sits on top of that. If the sales feed is off, every ratio is fiction. - Tightly integrated systems:

POS, inventory, and labour must share data reliably – via API or a central data hub. If they don’t, you get misaligned figures and operators stop trusting the numbers. - Continuous questioning:

When something doesn’t look right, they go back, investigate, and fix it at the source – whether that’s a mapping issue, an incorrect recipe, or a training gap.

“Garbage in, garbage out” isn’t a cliché for Patrick; it’s a daily operating principle. The goal is a world where operators can open a dashboard and say: “I believe this, and I know what to do next.”

Patrick’s advice to operators: stay curious, stay human

If Patrick had to boil his approach down to two principles, they’d be:

- Always stay curious.

- Ask “why?” – not to undermine people, but to understand.

- Keep digging until you can see how a number, process, or decision really works.

- Curiosity is what turns raw data into insight and better questions into better decisions.

- Never lose the human connection.

- Technology exists to support humans serving humans – guests, teams, franchisees, partners.

- Build real relationships with vendors, franchisees, and staff. Be the person who picks up the phone and expects the same in return.

- Use tech to make your people’s lives easier, not to replace them.

For Zeus Street Greek, the journey from 36 to 100 stores will be driven by exactly that combination:

- Operator-led curiosity about the numbers,

- A best-of-breed tech stack that actually talks to itself,

- And deep human relationships with the people who turn systems and strategy into hot food and happy guests, every day.

Ready to optimize your restaurant operations?

More stories from F&B leaders

Ready to transform your operations?

Join 3000+ restaurant operators cutting costs, streamlining operations and making smarter decisions with Supy.

.png)

.png)

.png)