Designing an Efficient QSR Kitchen: Stations, Flow, and Throughput

Most QSR kitchens do not fall apart because teams are not working hard enough. They fall apart because the kitchen was never designed to handle real volume.

Off-peak, almost any setup looks fine. During a rush, every extra step, shared surface, and unclear handoff gets amplified. Ticket times stretch, mistakes increase, and stress rises, even with experienced staff on the line.

That is why throughput matters. Throughput is not “how fast one person can move.” It is how many orders your kitchen can produce correctly per hour, consistently, without the operation breaking down. And the ceiling on throughput is usually set by the layout, not the team’s effort.

Chris Daniels (QSR veteran, Domino’s) summed it up simply: it all comes back to flow, and the goal is to reduce steps so people do not need to move when it gets busy. That mindset, flow-first, is the difference between kitchens that feel calm at peak and kitchens that feel like they are always catching up.

This guide breaks down how to design QSR kitchens around stations, flow, and throughput, with real-world patterns used by major brands and a practical framework operators can apply without turning into architects.

Throughput: the metric your layout is really optimizing for

Throughput is your kitchen’s ability to produce a high volume of orders with consistent quality and stable ticket times.

A few important realities:

- Throughput is constrained by the slowest step in the chain, not the average speed of the team.

- Adding staff does not always increase throughput. In tight layouts, more people can reduce throughput by creating cross-traffic and blocked access.

- Peak periods, not averages, reveal whether a layout works.

A useful way to think about it: every order is a sequence of small handoffs. If you reduce steps, reduce collisions, and reduce handoffs, you increase throughput.

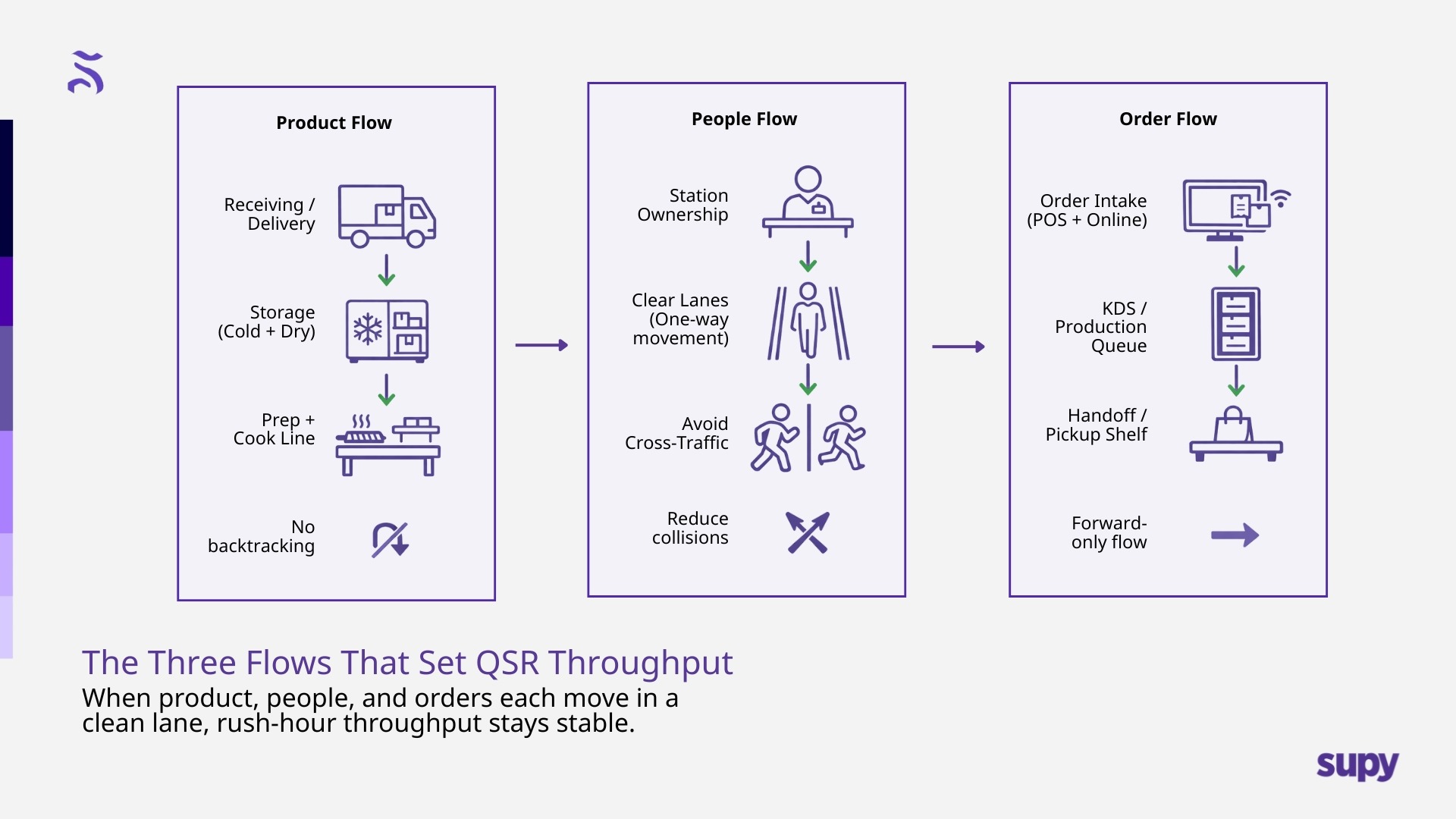

The three flows every QSR kitchen must get right

When operators say “layout,” what they often mean is equipment placement. What actually matters is how the kitchen enforces flow.

1) Product flow

How ingredients move from receiving and storage to prep, cook, assembly, and handoff. Good product flow:

- minimizes distance traveled per item

- avoids backtracking

- keeps cold chain and hot chain separated and disciplined

2) People flow

How staff move between stations, and whether the layout causes cross-traffic. Good people flow:

- protects station ownership

- reduces “reach conflicts” (two people needing the same tool, surface, or fridge)

- keeps runners and expediters out of the production lane

3) Order flow

How orders move from input (KDS/POS/aggregators) through production to the customer. Good order flow:

- moves forward, not sideways

- has clear handoff points

- protects rhythm, so one unusual order does not stall the whole line

If any one of these flows is broken, throughput collapses at peak.

Stations: Where throughput is won or lost

Most QSR kitchens share the same station families. The trick is not having them. It is designed so they do not fight each other at rush volume.

Prep station

This station determines whether the peak is smooth or chaotic.

Prep breaks throughput when:

- The prep team is physically blocking access to the line ingredients

- Prep is too far from storage, causing constant walking

- Prep is split across too many micro-areas, so no one owns the truth

Chris mentioned something very real here: modern QSR has shifted ordering heavily digital. That often allows operators to shrink “front-of-house order taking” space and reallocate it to production capacity. In new builds, that shift can be a throughput unlock if you reinvest space into flow rather than clutter.

Cook line (grill, fryer, oven)

Cook stations are throughput engines, but only if:

- Inputs are staged correctly

- holding is designed to support peak (without becoming a quality problem)

- The cook line does not become a traffic lane

Fryers commonly set the ceiling in chicken-heavy menus. Grills commonly set the ceiling in burger menus. Ovens commonly set the ceiling in pizza.

Assembly/expo

This is the most common throughput constraint in modern QSR.

Even when cook stations can keep up, assembly gets overloaded because:

- Too many SKUs converge at the pass

- Packaging and labeling happen “in the middle” rather than after the pass

- Delivery and dine-in orders share the same physical choke point

Packaging and handoff

Packaging is often treated like an afterthought until it becomes the bottleneck.

Packaging breaks throughput when:

- Delivery drivers crowd the pass

- The handoff point forces staff to turn around, squeeze past, or cross lanes

- Order staging is unclear, so staff are searching instead of producing

Common QSR layout patterns and when they work

This is practical, not architectural. You do not need perfect drawings. You need to understand the behavior each layout creates.

1) Assembly-line layout (the “forward motion” kitchen)

What it is: A linear progression from prep to cook to assembly to handoff.

When it works well:

- High-volume, repeatable menus where rhythm matters

- Teams that benefit from clear ownership and minimal decision-making during rush

- Drive-thru heavy operations where speed consistency is everything

Where it breaks down:

- Menu sprawl. The moment too many custom builds converge at assembly, the line loses rhythm.

- “Special items” that interrupt the flow. Chris described this well with Domino’s: certain menu items can stop the whole make-line and break throughput because the rhythm is the system.

Typical throughput constraint:

- Assembly/expo capacity (the end of the line becomes the choke point)

Brand cue

McDonald’s has long been associated with production-oriented kitchen thinking and has explored more flexible kitchen geometry to adapt restaurants to different footprints and expansion needs.

2) Galley layout (two parallel lines with a central aisle)

What it is: Stations on both sides of a narrow lane.

When it works well:

- Small footprints with high pressure on space efficiency

- Operations that need short reach distances and high labor efficiency

- Limited menu variation, or strong station discipline

Where it breaks down:

- The aisle becomes a highway. If runners, expediters, managers, and cook line all share the same lane, collisions become the throughput constraint.

- Poor placement of refrigeration and dry storage forces constant crossing.

Typical throughput constraint:

- Aisle congestion and handoff friction, not cook speed

How to make it work:

- Separate “production lane” from “support lane” if possible

- Move replenishment access off the main aisle during peak

3) Island/hub layout (a central production core)

What it is: A central hub for cooking or assembly with supporting stations around it.

When it works well:

- Flexible staffing models where one person can float and support multiple points

- Menus where components are shared and converge at a single build zone

- Operations where the hub is designed for multiple parallel actions

Where it breaks down:

- Too many hands in one space. The hub becomes crowded, and micro-delays add up.

- Shared tools and shared surfaces become hidden bottlenecks.

Typical throughput constraint:

- Human density around the hub and reach conflicts (space, not skill)

Brand cue

Wendy’s introduced a “Global Next Gen High-Capacity Kitchen” concept and has said it is designed to increase output capacity, including a dual-sided layout for higher demand sites. Wendy’s has estimated nearly 50% higher output capacity versus its standard next-gen design.

That is a classic “hub plus capacity expansion” design move: increase parallelism and reduce travel.

4) Zoned layout (hot zone, cold zone, assembly zone, delivery zone)

What it is: Separate zones for different production types, with clear boundaries and controlled handoffs.

When it works well:

- Multi-channel operations (drive-thru, dine-in, delivery) where order flow needs to be segmented

- Larger kitchens where you can protect zones from cross-traffic

- Menus with both hot and cold builds, plus high customization

Where it breaks down:

- Too many handoffs between zones

- Poorly defined responsibility: everyone assumes someone else owns the handoff

Typical throughput constraint:

- Handoff count and coordination

Brand cue

Burger King’s “open format” kitchen approach emphasizes visibility into prep and kitchen activity. That visibility often forces better discipline in zone clarity, because the kitchen is literally on display.

Separately, design coverage of Burger King prototypes describes layouts that support drive-thru performance, including double-sided line concepts and a smaller secondary line near the drive-thru in some designs.

The handoff count rule: fewer handoffs, higher throughput

A simple truth: every handoff adds delay and error risk.

In QSR, handoffs often multiply because:

- Packaging is separate from assembly

- Delivery staging is separate from packaging

- Multiple channels share one pass

- Managers “jump in” and unintentionally disrupt station ownership

A practical rule:

- If you need more speed, do not start by shouting, “Move faster!”

- Start by reducing handoffs and reducing steps.

This is exactly what Chris highlighted: when it is busy, you do not want people moving. You want them planted, executing a repeatable rhythm.

Prep placement is where waste starts, and throughput gets protected

Prep is not only a cost and waste topic. It is a throughput topic.

When prep is poorly placed:

- Line staff are forced to leave the station to fetch components

- Prep gets duplicated because no one has visibility

- Ingredients expire because par levels are guessed rather than controlled

- Replenishment interrupts the rush flow

This is also where brand operations become instructive. Chris described how Domino’s treats production like a continuous flow. Some QSR formats are linear, some are circular, but the principle is the same: design around rhythm and minimize steps.

If you are working with a central kitchen or commissary model, this extends beyond one store. You are designing a flow across:

- supply room and receiving

- commissary production and storage

- store-level finishing stations

- delivery, staging, and dispatch

Designing for peak, not for the average day

Peak volume is where layouts are revealed.

A practical stress test:

- Pick your busiest hour of the week.

- Write down your top 10 selling items.

- Map the route those items take through the kitchen.

- Count:

- steps per order

- number of handoffs

- shared tool touchpoints

- points where two people need the same space

Most bottlenecks are predictable once you map the reality, not the blueprint.

This is also where menu design matters. Chris shared a great operational truth: some menu items barely sell, but they can disrupt flow and stop the line. When you remove or redesign those items, throughput improves, and staff stress drops, without changing the kitchen footprint.

Quick wins without rebuilding the kitchen

You do not need a new build to increase throughput. Many improvements are layout-behavior changes. High-impact moves:

- Relocate the top 20 ingredients to reduce reaching and walking during peak

- Separate replenishment from production lanes (even if it is just “when”, not “where”)

- Move packaging after the pass where possible, so assembly stays focused on build accuracy

- Create a dedicated delivery handoff area that keeps drivers away from the make line

- Reduce shared tools (shared tongs, shared scoops, shared label printers) that create micro-queues

- Re-assign station ownership so responsibility is clear under pressure

The goal is not a prettier kitchen. It is fewer interruptions and fewer collisions.

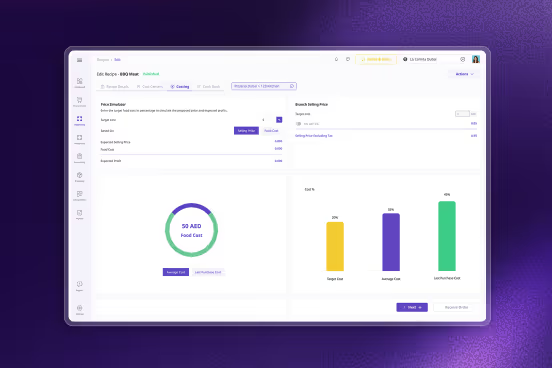

Where systems support throughput (without replacing operators)

Layout sets the ceiling, but systems help you sustain it.

The most effective QSR operators use data to:

- Understand demand patterns by channel and daypart

- Set prep pars that match reality, not intuition

- Identify which items cause bottlenecks

- Tie the waste and variance back to specific station behaviors

This is also where integrated back-of-house systems matter. When purchasing, inventory, prep, and recipes are connected, teams can see what is driving variance and fix the right thing, rather than guessing whether the problem is supplier, waste, portioning, or process.

Final thoughts: throughput is designed, not managed

Speed is not the goal. Repeatable output under pressure is the goal.

The best QSR kitchens do not feel calm at peak because the team is lucky. They feel calm because:

- Stations are designed with clear ownership

- Product, people, and order flow are protected

- Handoffs are minimized

- Prep and replenishment support the line rather than interrupt it

- The menu is engineered to preserve rhythm, not just variety

Throughput is designed long before service starts. If you design the kitchen around flow, you give the team a system they can win with, shift after shift.